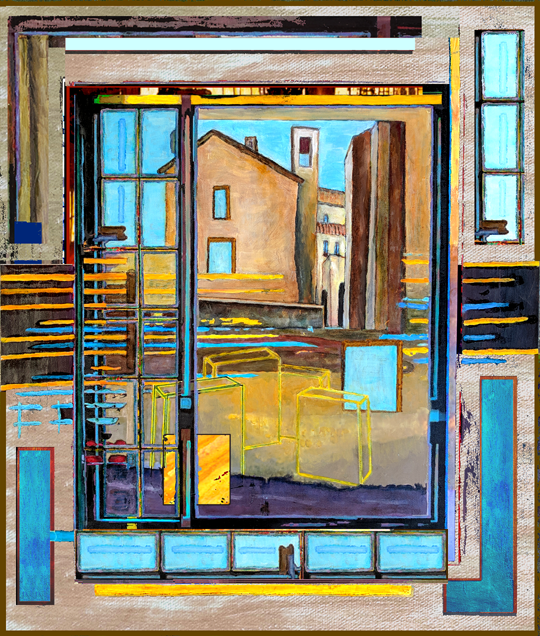

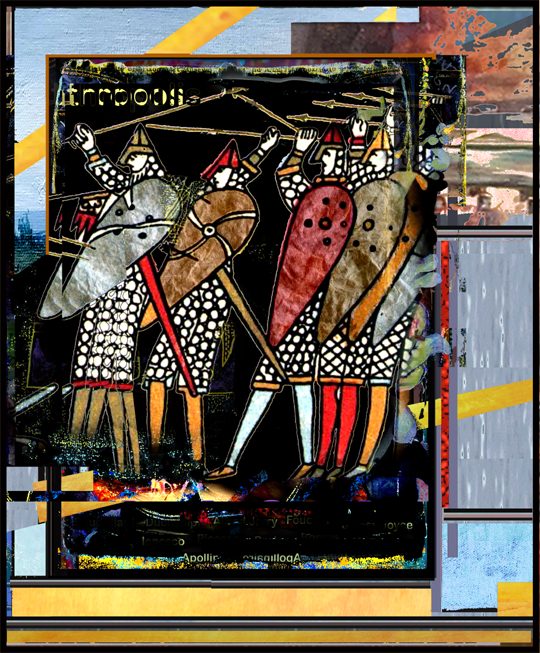

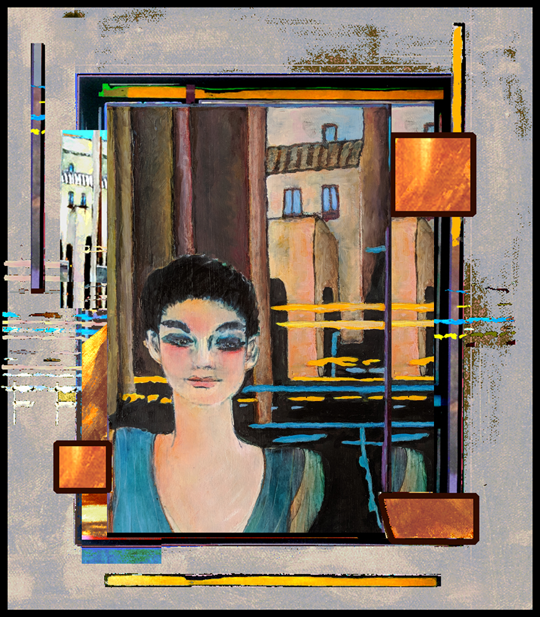

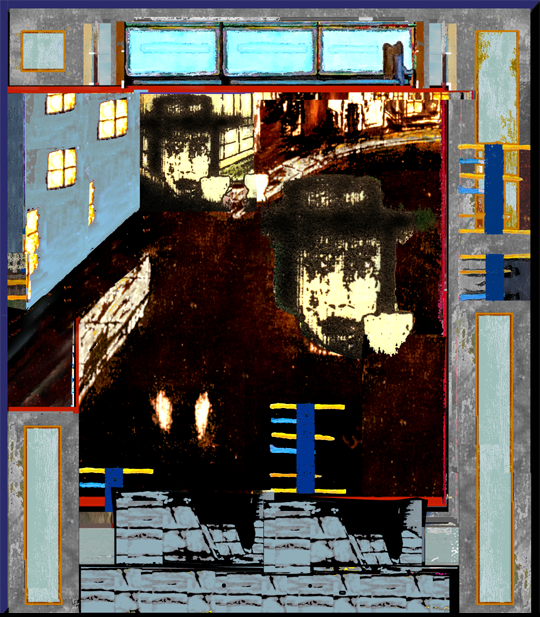

and that, or even Jarry’s pataphysics and the intentions of artistic integrity. But aside from that, many of these are representations of ordinary people, inside of highly-structured multi-dimensional spaces or suites. Given our contemporary situation, that’s a very obvious and engaging analogy. They’re visual metaphors and similes to the modern human condition: mutant Homo erectus ground-apes, now living inside a very complicated nest of different structures and different dimensions of conceptuality. Only two point five million years post Homo habilis.

Inexplicable Meaning and Ramanujan’s Astounding Mathematics

In defining that word, Silvershack was trying to peel the onion. Peel the outer layers off from the core of inexplicable meanings we sometimes get from successful visual art. It’s the abstract meanings which she finds interesting: inexplicable meaning. At the cost of being both oxymoronic and contrapositive at the same time: it’s a meaning we definitely experience but we don’t know what it means. Non-verbal meaning which can be felt, but not described. It might properly be called holistic meaning; but that imprecise word has been used way too much over the past half-century. Still, the phenomenon is categorically closest to rightbrain’s wheelhouse.

It’s a psychological problem, and a nebulous conceptualization. Like our conclusions about 1933 Nobel Physics laureate Erwin Schrodinger’s Cat: there is absolutely something there, but some critical aspects remain undefined: it’s a “superposition” of indefinite meanings.

Given the difficulties in explaining this inexplicable meaning, she refers to Ramanujan, the Indian math- super-genius. He was from very humble means, with very little formal training, but his abilities confounded Bertrand Russell and the rest of the famed and illustrious mathematics professors at Cambridge University in the early nineteen hundreds.

Mathematicians still marvel at Ramanujan’s seemingly-superhuman understandings and abilities; and are still trying to find rigorous proofs for some of his more important and difficult theorems. He could somehow recite sophisticated and undiscovered mathematical truths, but without having any way to explain how he knew them, or how to prove them to the trained Aristotelian faculty at Cambridge. Aristotle, the ancient father of Scientism, was the first “syllogist”. His logic of Linear Absolutism was a great triumph of the late-Neolithic.

Ramanujan said he received his astounding insights in dreams, whispered by Namagiri, a divine avatar of the goddess Lakshmi. This provenance of course, made no sense to the amazed Cambridge professors, but they did officially appoint him as a full-fledged Fellow, both of the esteemed Royal Society, and of the ancient Trinity College at Cambridge.

Ramanujan could feel the meaning of his perceived theorems, and he could very well outline their complex fundamental structures, but he couldn’t explain, even to himself, details of reasoning to support or prove his understanding.

7 In accord with Heisenberg, Gödel, Postmodernism’s “Incompleteness”, and the tenor of Collège de ’Pataphysique in Paris: pataphysical documents may have no formal beginnings or endings, second degree logic, meanings transmitted only in overtones - and per Jarry’s Dictum, reader/user input is often required to imagine more precise or informataive definitions for inherently inexplicit vocabulary and syntax.

The fact of these deep incomplete meanings, so obvious in Ramanujan’s example. This important understanding of something not understood. This, for Silvershack, is a model for talking about how chords of inexplicable meanings may be struck when a person has what she calls a mini-transcendental experience upon engaging with a successful work of art.8

It’s the same functional paradigm, she says. One can often perceive an indescriptive meaning or understanding while observing a work of art. Everybody knows that. That’s often why we look at art. Sometimes the feeling is earthshaking like Ramanujan’s insights were - and it naturally often feels somewhat important. Very often, she says, people don’t take much conscious notice of this interesting experience - due to the common left-brain practice of requiring names, labels, and verbal descriptions for anything which is to be consciously contemplated with focus.

In thinking about that indescript meaning, she breaks the experience down to a conflation of three quales: “very much”, “meaningful”, and “non-duality”. The impossible juxtaposition of those three quales nicely maps the base level of that experience: the inexplicable meaning one can get from viewing successful works of art. She wants to talk about that.

Combined studies show that a significant percentage of modern populations are overly-verbalized people who do confuse meaning per-se with tranches of verbal description, and who have trouble conceptualizing inexplicable or nondescript meaning. To them such a conflictable virtuality seems completely oxymoronic. Deficient for lack of some important advanced conceptual structures, but there we are…

Some paintings, for example, have simple and descriptable first level meanings. Consider all of history’s paintings with blatant memes of religious devotion, victory over an enemy, or just the soft and simple tacit appreciation of a vase with flowers on a doilied table.

Consider Jacque-Louis David’s monumental painting of Napoleon, riding his white stallion rampant. All decked out in war-silks, with his signature Napoleon hat, and metal finery. That 1801 painting is a surfeit of surface-level poignant and descriptive memes. Everybody recognizes that depiction of the rampaging Napoleon. Even now after two hundred years. It’s an uber-confident nationalistic celebration of victory. A celebration of the advancements and intellectual accomplishments of modern Enlightenment culture. This culture of French philosophy, the metric system, calculus, égalité, liberté, and the world’s first dedicated forward-looking encyclopédistes; all following in the great dictator’s wake.

Napoleon Rampant 1801

Jacque Louis David

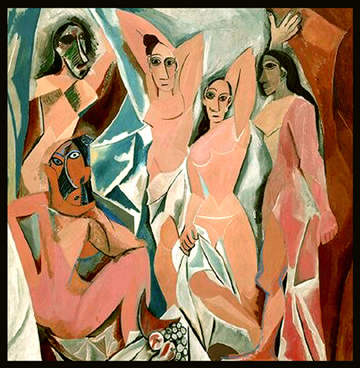

Demoiselles d'Avignon 1907

Picasso

8 She’s not arguing that these deep inexplicable meanings come only from observing successful artworks, and the whisperings of Lokshmi's divine avatar. She’s just making a focused observation.

That culture was imposed across much of the quickly-conquered late-Neolithic Europe by the dashing equestrian tyrant and his armies of soldiers, bureaucrats, and progressive engineers - both mechanical and social. Dashing Napoleon: the dictator who famously introduced the modern Nineteenth Century, by inventing and instituting the planet’s first modern police state. (Among his other accomplishments.) Per Johnson’s earlier extrapolated observation: if there’d been no Napoleon, there’d be no Faucault.

Plainly a contemporary denizen, familiar with the culture and current affairs of France at the start of the Nineteenth Century could have taken one look and delivered a lengthy description, listing several specific meanings or memes visibly posted there on the surface of David’s iconic classical portrait of Emperor Napoleon.

So then what about a Modernist work, Silvershack wonders, such as Picasso’s Demoiselles d'Avignon? Most cognizant contemporaries would agree that this is a very meaningful work of art. And the proof of that is in the pudding; i.e. ipso facto. But to describe the meaning of that 1907 Modernist painting, would be like taking a Rorschach test. It’s easy to describe the colors and visual details of the painting, and easy to describe one’s individual opinion of what various passages in the painting might represent personally. But that painting itself doesn’t describe or explain its own meaning. It’s engaging, but non-descript in that regard.

It was this consideration of Picasso’s Demoiselles as a Rorschach test that got Johnson to start thinking about her bandied conundrum regarding whether non-descript (or non-referential) meaning per-se is more of a meme or more of a quale.

Memes and Qualia

In the late 1800s Charles Peirce, a fellow of the erudite William James crowd, and known as the father of modern Pragmatism, invented the formal science of Semantics: the study of signs, and signals, and referential meanings. As part of that effort Peirce introduced the word quale in 1866. (Based on the Latin root for qual-ity.)

Quales, or more properly qualia, are the most basic sentiences or experiences possible, Silvershack says: like red, hard, hot, and high, etc. Neuro-psychologists have called qualia the alphabet of consciousness. They’re the leptons of experience, the smallest single chunk of sentient-awareness one can achieve. For example, per the mention above, the awareness or experience of red per-se is a quale.

One can be conscious of redness, and there’s no such thing as a part, fraction, or component of redness. Red is a quale. It’s basic and unitary. Conscious awareness of the quale red is integral to all possible ways of experiencing red per-se. And that quale is likewise integral to all experiences of red as a “quality” of some red thing. Or of some red-pigmented brush strokes in a painting, for example. Even to imagine something red requires a mental hyperlink with the quale “red”.

The quale red is automatically composed in consciousness with any hint of the color red: light-red, dark-red, warm-red, barely-visible red... They’re all composed with the quale red. And like the electron and its other lepton siblings, a quale doesn’t have any smaller components or parts. It’s fundamental and indivisible. All qualia are like that, and only that.

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the popular word meme in 1976. It essentially refers to a packaged unit of meaning which can be transmitted from person to person. To continue the particle- physics metaphor: qualia are the indivisible smallest particular chunks of conscious awareness; and memes are the complex molecules of meanings which are ultimately composed of clustered quales.

It’s interesting to observe how the Twenty-First century has linguistically adapted the word meme as a label for all those singular e-influences which are now flying around the internet in the viral billions. These instantaneous viral memes really are a significant new means of visual-verbal communication on the planet. They’re very interesting; in the same way that Johannes Gutenberg and bee dances are interesting.

Memes and quales are elements of holophysics; they’re virtual objects. They don’t exist in the same way that electrons and protons exist; and there’s no way they can be deeply investigated, or even properly addressed, by science or scientists. Such stuff is often quickly ostracized by contemporary canons of Scientism. But, ceteris paribus, these invented conceptuals can be very useful in thinking and understanding, even if they’re external to the palings of science.

Aside from Silvershack’s accusations of simple dishonest intercourse with brigands, the whole thing was possibly more about her less-consequential remarks - regarding the fact that art per-se is a relatively new phenomenon. The most we can prove is that art per-se9 has only existed in significant measure for about 36k years (since cave painting became popular in places like the Chauvet caves in France).10

Plato, on the other hand, famously thought that art as a concept has always existed; from the very beginning/ non-beginning of infinite everything. Whenever, or however that might have occurred. Plato’s holophysics – you can think about it, but you can’t address it.

Bruce Lahn’s MCPH1 – The Art Gene?

Though it’s mostly incidental to Silvershack’s focus here, some geneticists theorize reasonably that a brain gene11 designated “MCPH1” caused the mental mutation in humans which resulted in the beginning of humans making art. This gene was isolated and studied by University of Chicago, chaired professor of genetics, Bruce Lahn. By analyzing the demographic spread and the current statistical patterns in MCPH1 (as the numbers and mutating genetic alleles are observed from one demographic group to another) Lahn was able to show pretty conclusively to geneticists of the world that MCPH1 was acquired by the Homo sapiens genome around 37k years ago.

This new gene would have come either from a romantic affair with likely a Neanderthal12 sweetheart, or else possibly as a drastic, and very fortuitous, mutation of some previous sapiens brain gene. By looking at statistical regressions Lahn is able to show that whatever specifically this gene does, it gave its possessors a large survival advantage13 over other humans, and it spread like wildfire through the ancient tribes and clans in only a few generations. According to Lahn’s geno-statistical research.

9 (representational/referential art)

10 Humans were making colored handprints, and tracing outlines of their hand on cave walls

long before this, but that’s not really the same kind of “art” as a drawing of a bison, or the Portrait of Whistler’s

Mother.

11 Lahn can’t yet say specifically what this gene’s function is, but he is certain that one of

its main jobs involves some kind of significant brain operations.

12 By the time the Neanderthals went extinct, about 40 thousand years ago, we had been

sporadically intercoursing and swapping genes with them for an estimated 10 thousand years. About two to four

percent of our current sapiens genome was inherited directly from Neanderthals.

13 Lahn doesn’t speculate what this advantage is, just that possessors of the gene were a lot

better at surviving and passing on their genetic identities than were the non-possessors.

Given statistical overlap, and reasonable margin of error, it’s easy to say that Lahn’s brain gene entered our genome about the same time that we finally see evidence of art per-se in places such as the cave walls at Chauvet. Not that coincidence proves cause, but a significant new brain gene coincident with the beginnings of art is at least something interesting to contemplate.

A popular Latin aphorism distinguishes the word ars, as specifically connoting art per-se14. It’s interesting that English vulgate possesses an exact homonym, but with quite a different etymology. Explaining this here with Freudian art theory and some kind of onomatopoeia15 would be an unreasonable stretch, but Freudian toilet humor is always worth at least a mention. Especially when so many people are familiar with some of modern psychology’s scatological theories of where psychologically the impulse of art-making comes from: ars.

Silvershack’s approach is more metaphysical, and perhaps more anthropological, than Lahn’s focused laboratory researching of molecular machinery. And she has obviously investigated a range of philosophical crannies, asking such questions as why in the last century and a half, after 36 thousand years, we’ve suddenly come to accept completely non-narrative, non-representational, abstract colored shapes on canvas or whatever, as high art. By some definitions16 a lot of this modern abstract art is completely non-referential.17 One hundred percent reference-free. A completely new arrangement for subject and object. Such stuff was never before considered to be art. Some of it was crafty object-decoration maybe, but not high art.

The Apperceptions of 1850

Silvershack asks why abstract art in particular is so interesting to genus Homo, but is of no interest at all to our closest cousins the genus Pongos and the Pans. Going deeper into the beginning point of human art per-se, she sees an informative parallelism between this very beginning of art itself, and how our present-day culture recently evolved to engage with abstract art. To her, one of the most interesting aspects of all this is the ongoing fits and starts of the transition process, as our culture slowly absorbs the quakes which are making possible our acceptance of non-referential abstract designs as pure high art.18 A Century or more in the unfolding; it’s a momentous psychological stepping stone..

In 1850 nobody would have agreed that a good painting could possibly be just some non-representational geometric forms or random scribbles on canvas. It had always been agreed that the art of painting is inherently representational. A denial of that had never even been substantially conceptualized. It’s not something one would have considered to think about. But then, as Johnson notes, the appreciation of pure abstract art is currently enjoyed by only a fraction of our contemporary population. The rest of us, often derogatorily referred to as “the philistines,” still share many of the tastes and apperceptions of 1850.

14 Ars est celare artem. (Art/artfulness is the act of hiding/concealing artifice.)

15 See V. S. Ramachandran’s theories about hard-wired onomatopoeia, and his research on

the famous Bouba / Kiki Effect. His research has proved that synesthesia actually does exist, and that certain

shapes at least do have hard-wired onomatopoetic connections to particular audio phonemes.

16 and according to much insisting by some concerned artists and critics

17 The influential Abstract Expressionist Hans Hoffman like to brag that his abstract

paintings actually were properly representational because, even though a viewer wouldn’t consciously notice it, his

subjects were always things he was looking at in “nature”. In response to his bragging and criticism, Pollock

declared “but I AM nature”.

18 “Pure art” being tangibly different from abstraction which is just decoration on some

object of utility.

Obviously, she says, the somewhat-popular theory of Lahn’s gene being responsible for Chauvet is simply speculation based on likely coincidence. But she stresses that somewhere between Australopithecus and Paleolithicus there almost had to have been a genetic upgrade of some kind - which led to the large numbers of sapient Paleolithic apes suddenly scratching out referential visual representations on rock walls, and then painting them. Creating and appreciating art in their dank rocky nests.

It’s against this context that she hypothesizes the possibility of researchers in the future discovering a gene which statistically differs between those who appreciate and create abstract art, and those who don’t. Maybe there’s a mutated gene involved; just waiting to be discovered and described by A.I. or maybe some future professor Lahn. Or maybe not. After all, they say there are only two kinds of people in the world. Those who believe there are only two kinds of people, and those who don’t.

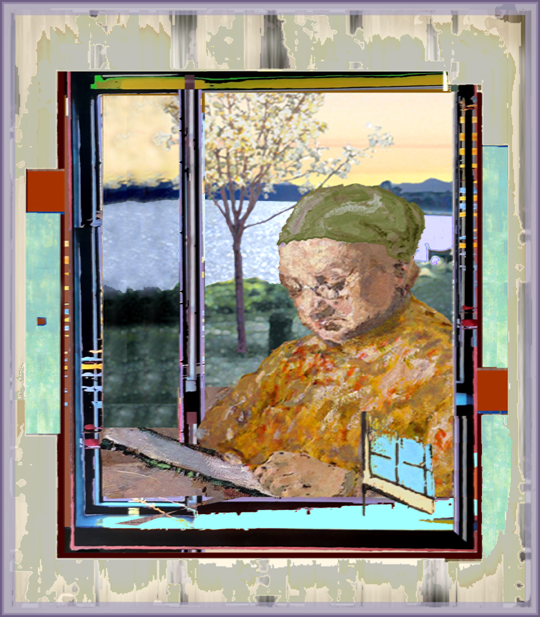

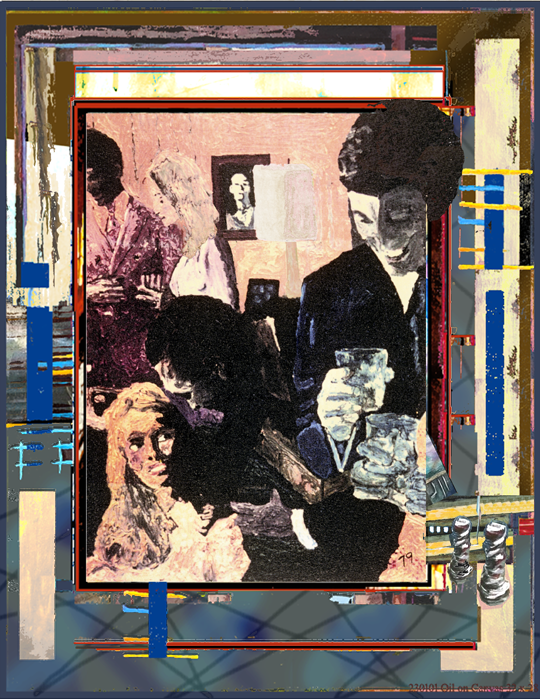

Johnson’s Hominid Structuralism

Johnson’s reputation improved significantly upon her public opining that the species can reasonably be divided into the two basic categories: those she labels the emotionalists, and opposing them, the complementary structuralists. In accord with that, she’s now suggesting that a large percentage of the most engaging popular paintings throughout western history are likely to fit the definition of what she neatly calls Structuralist ad Hominem, or Hominid-Structuralism. To qualify as such, a painting has to make strong reference to an organizing structure of some obvious type (enough to reasonably be called Structuralist). This depiction of structure might be just some strong geometric forms in the painting, or perhaps the composition features prominent parallels, or orderings of some other sort. Or the structuralist part could even be a painted narrative reference to some poignant social or cultural structure: religion, laws, cause-and-effect morality-tale, etc. Any reference to conceptual or haptic structure. Note that her outline includes several varied paradigms by which painters have represented structures of many different types and flavors over past millennia.

And then aside from the structural references: to fit her definition of Hominid-Structuralism a painting must feature domestic, or other humanistic memes: people, comfort food, heroism, music, the farm, a home, etc. She offers as a primary example Vermeer’s many paintings of populated domestic interiors. Their structured spaces are organized and highly regulated by Vermeer’s visual rectangles and other parallelograms outlining the floor tiles, walls, windows and furniture. And then they’re populated with homespun mothers engaged in some familiar domestic activity; they’re very hominoid. Big references to structure, and packaged up with engaging humanity – obvious examples of Johnson’s percipient definition.

Lady at Virginal with Gentleman 1665

Vermeer

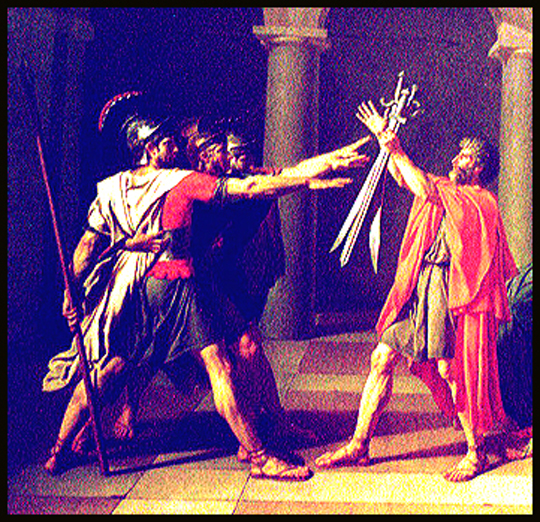

Oath of the Horatii 1784

Poussin

Cubism and The Oath of the Horatii

The early Cubism of Picasso19 and Braque is also offered as exemplary of Johnson’s definition. As their movement name suggests, physical realities are reduced to their fundamental structure: lines, shaded planes and geometric solids. Following Cézanne’s foundational interest in structuralism, Picasso and Braque were foremost in making structural considerations the sine-qua-non of their art. But these early Cubists also commonly featured such things as prominently-referential S-shaped curves, sets of a few straight parallel strings, and black disks, all of which in context were clearly representative of violins and music. Hominoid references. And several of their best-known paintings included collections of abstracted geometry which were complex but which parse out to be recognizable candlesticks, and light in the nighttime. Structure coupled with evidence of human comfort and enjoyment.

19 Like so many other Modernist painters, writers (James Joyce for example), and composers (John Cage, Paul McCartney), etc., Picasso’s art was heavily influenced by his friend Alfred Jarry’s pataphysics, and its radical ideas about rationality in culture and art, viewer participation, and new relationships between subject and object.

According to Johnson, all bicameral hominids, in their own ways, are naturally and endlessly curious about quales and memes both of structure and, as well, of any reference to hominoid passages of whatever kind. (“Structure for the left-brain and humanistic passages for the right-brain”, she says.)

And she points out also Poussin’s iconic Oath of the Horatii, painted about a century later than the Vermeers. That painting is famous for two kinds of structural reference. First is the visual power of geometric triangles formed by the legs of Horatio’s three heroic sons with their three raised swords. And secondly the familiar reference to the rigid Roman moral codes regarding patriotism, duty, family, and loyalty, which the Horatii are highlighting in the conflicted historic moment they portray. (It’s from an ancient Roman morality tale which was well-known in Poussin’s time and place, at turn-of-the- century France.) And then there’s the domestic heartstring tugging in Poussin’s depiction, off to one side, of the Roman warriors’ poor loving sisters and wives, despairing of the immanent war. Heavy structure, heavy poignant humanity.

While Silvershack finds the nexus of Johnson’s “Hominid Structuralism” as informative to the investigation of Modernism per-se, she nonetheless finds it ninety percent derivative. It doesn’t duplicate, but it’s very reflective of how painters since the Italian Renaissance have traditionally been divided into either the emotional Colorists practicing Colorito or else the structuralists practicing Designo. Two different kinds of painters.

Colorito, Designo, and Tout Le Monde

Once the practice of painting had become elevated in the Renaissance to an unprecedented high and studied art, Italian painters and art critics noticed that painters and paintings could be divided into two mostly-exclusive categories. Firstly, those where the painter is concerned most with presenting emotion and attitude through the careful expression mainly of color. These are the practitioners of Colorito, Reubens for a prime example. Secondly are the practitioners of Designo, who will do a mostly un-thoughtful, though adequate, job of coloring but who are mainly concerned and engaged with the lines and shapes of the represented subject; Poussin is the traditional example.

But consider in that previous regard, the so-called Modernism-Postmodernism “kitsch” debate. Particularly the fact that the Modernism movement in art, like Mannerism, and Minimalism, is defined by a fairly specific set of styles, flavors, and theories.

And consider that the fact of a painting, novel, or sonata, etc. being completed in modern times has no bearing on whether or not it qualifies as part of the intellectual philosophy-of-art conversation which is recognized as Modernism by tout le monde,20 i.e. the art crowd, the literati, the criterati, the cognoscenti, and the art-history books.

As one might predict, Johnson’s fourth assertion regarding the exigencies of PostModern art theory is the whole issue of “kitsch” (which derives from the Nineteenth Century’s invention of mass-production). As discussed previously in some detail: this burgeoning practice of factories cloning objects by the thousands or millions produced a should-have-been-expected sociological assault on individualism. This sudden in-your-face endless cloning of household objects; mass production of identical toy dolls, tin bread boxes, and framed Bouguereau prints, for example. (Everybody everywhere suddenly has identical accoutrements.) Even Monet’s repetitive painting of Rouen Cathedral has been seen as reflective of this. It all raised uncomfortable problems for Western society’s philosophy of and understanding of art; as well as for issues of broader culture in general. And for the societal understanding and concurrence of both collective and individualist identity as modern, post-Neolithic humans.

Cookie-Cutter-Culture, Identical Replaceable Parts, Generic Identity

Eli Whitney, the inventor of the cotton gin, is often credited with single-handedly inventing factory mass- production of interchangeable parts, and thus sparking the modern industrial age in 1801. Significantly it was the same year that Jacques David painted that portrait of charging Napoleon. Before that time rifles, for example, were hand-made by skilled artisans, one at a time, one single piece, one component, after the other, (like all other manufactured goods in those days). And the parts of one rifle were not replaceable by the hand-made parts of the next rifle. In the two-point-six million years since Homo erectus invented the hand-axe, humans had always retained the old way of looking at things, and just never conceptualized mass production of identical, replaceable parts. Or if somebody, somewhere, did get the idea way back when, then it still never caught on until the early 1800s. Sapiens just weren’t ready for that kind of thinking yet, obviously.

Gun making in the year 1800 was a very slow process and there was no way the American Congress could obtain anywhere near the number of muskets they desperately wanted for their brief war with France. Whitney contracted with Congress to produce ten thousand muskets in an impossibly short amount of time. When he couldn’t deliver, he met with Jefferson in 1801 and astonishingly demonstrated himself quickly assembling a complete new rifle from boxes of identical mass-produced parts. President Jefferson was stunned and only a short time after that Whitney famously ended up delivering fifteen thousand new mass-produced identical rifles in only four years. That was an earthquake. Mass production and assembly lines quickly exploded around the world from those early eighteen hundreds.

In recognition of the now-ubiquitous cookie-cutter culture which Whitney instigated, his personal achievement in the history of hominid weaponry is sometimes compared to the Homo-habilis invention of hand-axes, which anthropologists date back over two million years. It is true that both innovations created instant earthquakes in human culture. All of a sudden, a couple of million years ago, everybody was carrying around a weapon, a hand-axe, wherever they went; and now, by grace of Whitney, a mass-produced gun. Or if not a gun, they do all carry around some other of the thousand very different and affordable mass-produced everyday hand-tools; such as ball-point pens and dime-store hammers. Both of these events were giant jumps in the evolution of human weaponry or tool-use. Both of these inventive cultural icons have large and perusement-worthy pedestals in the Michel Foucault Virtual Museum of Hominid Power-Multipliers, hosted as one might expect at Berkeley.

20 In Tom Wolfe’s definitive little book about the current culture of High Art, he explains how that high-tone world of artists, collectors, museums and critics refers to itself as “everybody”, or to be a bit more snooty: tout le monde.

Rouen Cathedral

But returning to northern France, and Claude Monet’s work at Rouen: laboring at his famous series of paintings of the great cathedral’s highly-decorated façade, over and over again, between 1892 and 1894. He painted each of those canvases at a different time of the day, in different weather, in a different season; in different qualities of light, in different resolution and focus, and thus different moods and styles ancillary to those qualities. But significantly, many of the moods, modes, memes and quales Monet presented in these paintings were mostly mediated artist exploration, rather than referencings or representations of actual weather at the cathedral, or of different qualities of actual sunlight and cloud.

Monet painted the same subject over and over again, but the exact object of each painting is to demonstrate a different way of looking at things. To explore the expression of a particular unique mood, mode, meme, style, feeling, or attitude. Each one very different, from one painting to another – in object, but not in subject. Like no artist ever before, the incipient Modernist, Claude Monet, was carefully studying the difference between the subject and the object of a painting – and observing that the object of a work may have basically no significant relationship to the subject. No other relationship beyond the simply circumstantial – the kind of feckless and purely-putative relationship Vonnegut describes in Cat’s Cradle as a “Gran Falloon”. Again, some critics theorize both a reflection of, and a harbinger of kitsch, here in Monet’s repertory paintings at Rouen.

Finnegan’s Wake

That re-paradigming of the subject/object relationship was a fairly radical idea, and one that would soon take root in many various enterprises and entanglements of Western arts and letters. Consider for example the extreme Modernist works of James Joyce, John Cage, Duchamp, the Minimalists, and Michel Foucault. Johnson of course recommended many years ago that one may quickly get a sufficient visceral understanding of this issue by merely attempting to conflate Joyce’s object in his groundbreaking Modernist book, Finnegan’s Wake, with the subject of that same book.

The object of Finnegan’s Wake is manifestly the semiotic science of memes (or the fundamental chunks of meaning in human experience), along with exploring and demonstrating linguistically how various-sized memes of meaning can be promulgated with groups of words. In other words: the object of Finnegan’s Wake is a Modernist study of the basic means, methods, and tools of the art of language itself. Ipso facto: lorem ipsum.

And as Clement Greenberg, the New York art critic, arbiter of Abstract Expressionism, and mentor/promoter of Pollock, so poetically explains this - it was not just Monet, and Joyce. (Already in Alfred Jarry’s time this same new Modernist paradigm was manifesting and moving in all kinds of the various arts and letters, and in the absinth dens of Europe.) Greenberg explained this so parsimoniously about Modernist art being self-focused and objectively just mainly about art itself:

The best artists now are artists’ artists.

The best sculptors are sculptors’ sculptors.

The best painters are painters’ painters, and

The best poets - poets’ poets.

(One of the most elegant and reflexive of the Greenbergian haikus.)

Impressionist Inversions

Monet recognized that the object of a work could ignore the subject and address instead some fostered contextual, such as the artistic visual tools and methods one might personally use to express not an isomorphic photograph or perfect representation of a subject, but an exceedingly-large-grained and abstractly-pigmented Impression of some significant meme, mood, attitude, emotion, or ethic, etc. Technologically a new way of painting and representing the world; and the undercurrent, though somewhat difficult to parse, was distinctly a significant new way of looking and thinking about things. It’s hardly a wonder that these painters were rejected for so long by the establishment.

That new way of thinking about things was also informed by the empirical methodology of the Impressionists’ project. Significantly, James Maxwell had just recently shocked science by discovering the elegant mathematics and the sin-waves, which explain and bind together: electricity, magnetism, light and color. Photons are electromagnetic phenomena.

Impressionists and others researched the physics and neurology of color: how color perception works, how semi-digital dots of pure primary colors can contextually meld into perceived Impressions of reality. How the eyes can knit together meaningful impressions from the context of colored bits or blots. To their eyes it was digital. Discrete “bits” of color. It wasn’t twenty-first century physics and neurology, but it was a huge shift from the 1850’s traditional analogue paradigms of art, as well as from the general culture’s analogist world-views and linear Aristotelian conceptual methodologies in general.

Art That Represents Nothing

In any case, aside from his other pioneering of the Impressionist movement, Monet was simultaneously introducing this fundamental theme of Modernism: that the object of art itself may be different than the subject. The object of a work doesn’t have to be simply a representational of some subject. As late pluperfect Modernists like Duchamp21 and the Minimalists, and like Jackson Pollock demonstrated, art actually can just be itself, and represent nothing.22 To represent absolutely nothing. The cognitive subject of the art is null. The traditional representation and illusionism of past painterly practice and two-dimensional art are completely extirpated.23 Such observations as the following were repeated ad infinitum by the New York critics:

“The object of Pollock’s drip paintings is simply Modernist exhibition of the inherent nature of paint. The medium comprising ars24 ipsum, the art itself. As this genius work so boldly demonstrates: the nature of paint is to drip, and to splash! Jackson’s art, as Greenburg notes, is about letting his means and medium just do their thing, representing absolutely nothing; with as little artem, artifice, and artist-fabrication as possible!”

21 And in thinking here about the complexities of subjects and objects in Modernist art,

consider Duchamp’s “Readymade” store-bought snow-shovel “sculpture”, which by its title the “artist” tells us what

subject it represents: In Advance of a Broken Arm.

22 Consider for example Minimalist giant Carl Andre’s copper tiles, rejecting representation,

and doing what tiles naturally do by simply laying flat on the ground, titled 100 Copper Squares (1968).

23 Unless you argue obliquely, for example, as one New York critic did that the viewer can detect

a smidgeon, a soupçon, just a hint perhaps of three dimensional space in Pollock’s canvases. “The careful viewer will

notice that darker drips of paint tend visually to recede just a bit and push the lighter colors slightly into the

foreground. And thus Pollock’s paintings are indeed representational (if only by the slightest suggestion of 3-D

space) and he is therefore not the perfection of Modernism after all.”

24 Ars is the Latin nominative case (and Artem is the accusative, which idiomatically can

indicate artifice).

It’s interesting how concern regarding the word or concept “artem” (skilled fabrication) was radically different in ancient Rome than it is with Greenberg and Pollock’s Abstract Expressionism. The Romans insisted on hiding the artem (markings of the fabrication process), because it detracted from the realistic representation, and it sucked attention from the subject of the painting or sculpture. Ars est celare artem. Greenberg’s Modernists on the opposite hand were attempting to completely eliminate the artem or craftsmanship itself - not just hide all the traces of it. And for a very different reason. They were trying to make pure, non-representational art; something that wasn’t crafted by some deficient human disturbance of natural things. They argue that a piece of art should express the inherent nature of the medium itself, rather than the representational intent of a human.

As Rene Magritte so pedagogically explained, a pictured representation of a smoker’s pipe is not a pipe itself. He’s teaching from the Late Modernist canon that representational art is dishonest illusion. Pollock, Joyce, Cage, Foucault, and so many other Modernists agree completely with all that - honest art must be about the means and medium of its own making, and not a representative of some external subject. And that’s analogous to the human psyche, of course. Accordingly, the high Modernist praise of Pollock is that he is representing nothing, and just lets the paint do its natural thing: drip down and stick to a piece of stretched canvas.

These ideas about representation, and subject and object, are of course in the small handful of permanent definitive issues for the Modernist movement.

Magritte’s picture of a smoker’s pipe is specific, regarding the fundamental nature of representing a thing in a painting. (Or in any other representationism, in any other artistic medium.) It was a tangible way of addressing a slippery question which was troubling (or at least intriguing) the art community. In 1929 Magritte painted his iconic work, known on the street by its own statement: Ceci N’est Pas Une Pipe. To guaranty that viewers all understood the statement he was making about the hot issue of representationism in Modernist art, Magritte neatly titled the piece The Treachery of Images. Magritte’s double-coded comment about the intent of the piece is:

“The famous pipe. How people reproached me for it! …it's just a representation, is it not?”

Repertory Painting

Monet is sometimes credited with, or accused of (depending on one’s perspective) being the first modern “Repertory Painter,” i.e. one who puts interchangeable parts into their paintings. Like repertory theater or music: the artists present the same chunks of art over and over again, just maybe tranched up in a different tenor or an altered arrangement. Monet worked up a batch of different paintings, each containing a plug-in appearance of the same brick and mortar cathedral façade. Most arguably cookie-cutter, and repertory.

Monet wasn’t specifically enamored of the Rouen cathedral, (nor for that matter the haystacks at Giverny which he also painted repeatedly as part of this redundant series during the fall and winter of 1890). Though his painting in these repeating recursions might risibly be argued to border on Obsessive-Compulsive disorder, it was not at all that he found the subject of his painting so engaging or particularly significant. His objective with the haystacks was identical to his objective with the Rouen paintings. Monet’s two subjects in this series were merely incidental to his objective studies of the art of painting itself.

Rodin's Infamous Repertory Crowdsourcing

Rodin’s famous repertory work wasn’t empirical or didactic like Monet’s; it was just utilitarian. It was mostly a convenience for Rodin, and a savings of time and expense. Rodin was roundly roasted by many of his contemporary art critics for the insults he inflicted on the theory and practice of art itself (ars ipsum), with his vulgar manufacturing processes, as well as for crowdsourcing his imagery. Imagine looking at Rodin’s unfinished but epic Gates of Hell for the first time and realizing that Adam’s right arm was not Rodin’s work but had been copied from Michelangelo’s depiction of God on the Sistine ceiling; and his left arm was bronze copy of an arm depicted in Michelangelo’s Pieta. Copywork art, by contemporary definition non-creative.

Of course now after the acceptance of Duchamp’s readymade urinal we contemporaries can’t imagine how the art world a dozen decades ago could have conceived of artwork which itself is inherently an impious insult to ars ipsum. Those were the days of right art and wrong art, good art and bad art, good artists and bad artists – all determined by a small priesthood or academy (cabal) of establishment elites and professors.

Bronze sculpture lends itself to repertory art; because the required molds for parts naturally suggest the ease of another duplicate casting. Bronze sculptors have always made multiple identical copies. But Rodin had no sense of propriety, or restraint. For example he would take an additional bronze arm from one of his shockingly-good sculptures and weld it onto the bronze body of some other person, making a pastiche or hodgepodge, in principle, of both works. He duplicated some parts from his epic Gates of Hell, for example, and used them as major elements of other completely separate works.

Many viewers and critics were outraged. How could the great sculptor of the age cheapen art like that; lazily bricolaging pieces together from his manufactured leftovers? Dishing out the same piece of art over and over again, as though nobody would notice. How were these cobbled assemblages anything different from the kitschy ten-cent printing-press replicas of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa which peasants everywhere had hanging on their dirty cottage walls.

In his famous essay about the sculptor, Leo Steinberg, summarized how so many of the critics felt that due to his violating the canons of art production:

"Rodin's method seemed little more than a game of mix-and-match, lacking the seriousness expected of high art."

Critic Albert Elsen, in his book Rodin's Art, cited how he was accused of:

“repeating himself" and "piecing together" fragments in a "thoughtless" manner.

Johnson, of course, tends to dig a bit deeper, beyond the obvious facts of how Rodin crowdsourced his work from passages by previous artists, and mass produced repertory pieces from his casting factories - in favor of considering new and deeper societal and cultural forces affecting not only the disputed apotheosis of Rodin himself, but also and more importantly the fundamental radix of

22 Torczyner, Harry (1977). Magritte: Ideas and Images. p. 71.